Review: There's No Turning Back

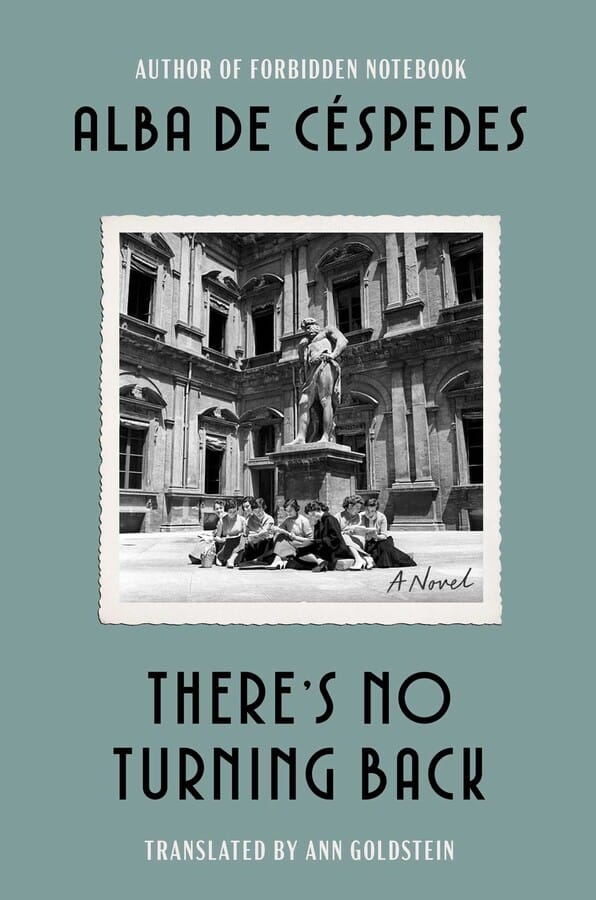

There’s No Turning Back

Alba de Céspedes, trans. Ann Goldstein

Washington Square Press, Atria, February 11, 2025

Without opening the cover or cracking the spine of Alba de Céspedes’s 1938 novel There’s No Turning Back, it was pretty much a given that it would be banned by Benito Mussolini. Being an antifascist woman who does antifascist things in Fascist Italy would be enough even if the book were about a puppy who admires, I don’t know, daisies. Start reading Céspedes’s novel, newly translated by Ann Goldstein (also Ferrante’s translator), and the reasons that a Fascist dictator might want to ban it become evident.

The story swoops and circles around and among eight women rooming at a boarding house run by nuns in Rome. They are all in the city ostensibly to attend university; a couple of them are only using school as cover for other activities, a couple of them have their attentions turned elsewhere as global events overtake their personal lives, and one is a devoted academic intellectual. These women have the audacity to be flawed, to be figuring things out, to make serious mistakes, and to not be punished. They have their hearts broken, they make the best of shitty situations, and they stride forward after horrible failures. But God does not smite them, and they are not cowed. This is revolutionary stuff.

Céspedes’s style has been described as experimental, and I’m willing to bet it was when the novel was published. Others who have read pre-War Italian novels will know better than me. But as a reader picking this up fresh and largely unaware of the book’s literary context, it seemed like it could have been written in the past five or ten years. She uses a technique more reminiscent of a streaming series with multiple main characters and plot lines rather than a straightforward single-protagonist narrative. If I tried to describe it to you, it might seem chaotic or confusing, or like an editor’s nightmare in an omniscient novel: head hopping. But her use of this particular omniscient technique is not only clear and easy to follow, I think it might be easier for modern readers to follow than it was for audiences in her own day (if they could even get a copy of the book).

Like many “experimental” techniques, such as stream of consciousness, it might be disorienting at first, but the reader quickly acclimates and settles in. Here’s one of the best examples, a passage about Milly, who is studying music and deals with a chronic illness:

One night Emanuela didn’t come down to join her friends in the parlor. “She’s with Milly, who’s ill,” said Anna. “If Milly doesn’t get better we’ll have to give up having some nice Christmas music.”

In Milly’s room the lamp, shaded with blue paper, gave off a pale glow. Milly was sitting on the bed, her hair loose over a soft wool jacket. She started, hearing someone enter, but when she saw Emanuela, she said: “Come on in. I was just reading.”

She wasn’t holding a book and, besides, she couldn’t have read in that light. Then, approaching, Emanuela saw that she had a sheet of paper in her hand.

The paper is from her boyfriend, who is blind, and it is in a kind of Braille, “covered by small holes with raised edges.” She tells Emanuela that she must go down and practice the oratorio that she and her boyfriend have promised to play at Mass, and she explains how terrible the flareup of her illness had been the night before.

She went back to running her fingers over the sheet of paper, staring into space. The doctor had said: “It could be now or two years from now.” Her friends entered on tiptoe.

In this passage, Céspedes begins with the women in the parlor wondering where Emanuela is. The “camera” cuts to the interior of Milly’s room, where the reader is given a description of Milly as if viewing her from a hidden corner. Then we see her startle as Emanuel enters. We now see her from Emanuela’s point of view: Milly has said she’s reading, but the light is dim and there’s no book in her hand. After Milly describes the letter from her boyfriend and her most recent bout with her illness, the “camera” returns to the point of view of the disembodied observer in the corner, or maybe Emanuela, as Milly reads with her fingers. But then, crucially, the reader is allowed inside Milly’s head, a kind of interiority impossible on a screen, as she remembers her doctor’s fatal pronouncement. Just as quickly, Céspedes returns us to our position outside Milly’s mind as her other friends come in.

The entire novel is constructed in this way, with a narrator who swoops like a bird from scene to scene and character to character, endowed with the ability to occasionally eavesdrop on their innermost thoughts and emotions. Rather than feeling erratic, it allows Céspedes to drop tiny bombs, like the fact that Milly does not have long to live, that have that much more impact when they land on the reader.

Céspedes has a way with the tiny detail that encapsulates an entire situation. Vinca has come from Andalusia in Spain to study, and one night she tells Emanuela that the fighting in the Spanish Civil War has erupted yet again.

Papa wrote that, just as a precaution, he and his wife are leaving the city, going to the countryside. We have a house near Cordova: if I go back, you have to come see me. It’s a cottage, you know?, but sweet because my grandparents lived there, and it has beautiful furniture from when we were rich. Everyone was wealthy once, even us.

There is so much about Spain during the war packed into this short passage. Things are serious enough that Vinca’s parents are seeking safety. She herself hopes to return, but that “if” shows that she’s not sure that she’ll be able to, or whether what she returns to will be the same when she arrives. The family has a cottage in the country to flee to because it once belonged to her grandparents and they were able to keep it—with all its furnishings—even as they moved to the city as Spain, like other countries in the early twentieth century, became more urban. Goldstein as translator does well to retain that perfectly natural “you know?” in the middle of the sentence, letting Vinca’s voice be her own. And then there’s that final line, about which you could write an entire essay about nostalgia and longing for things that may or may not have ever been true during times of upheaval.

These women are finding themselves and find out about themselves and learning how others see them. Céspedes often mentions that someone gestures like a woman, or because of the way she is dressed is not a woman, or is considered too ugly to be a woman, or she smiles like a woman. There are less frequent but similar ways of identifying manhood. Over the course of the novel, by following eight very different young women in 1930s Rome, the reader pieces together what a woman must be—and, as always, realizes the composite is a cubist fantasy that cannot be attained by any living woman. It’s a tale as old as time and as relevant in 2025 as ever.

All links to Bookshop.org are affiliate links that help keep The Wingback Workshop working. Thank you for your support!